Can a product be “carbon neutral”?

Whether a product can be “climate neutral” is an interesting and complicated question. Our take is this: If the life cycle of a product leads to a net release of greenhouse gases, the product should not be referred to as “climate neutral” even if the emissions are compensated with carbon offsets.

What is carbon offsetting?

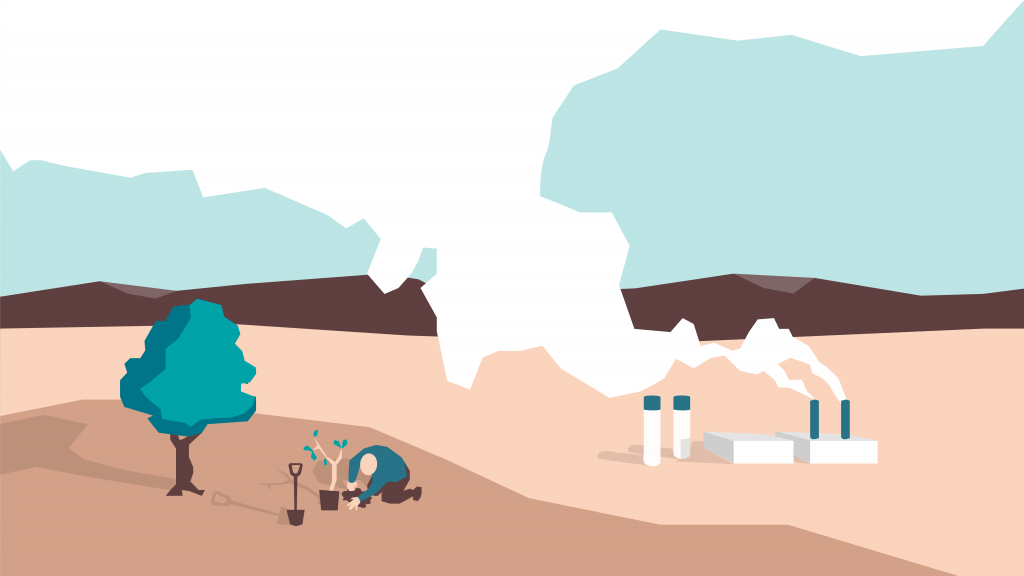

Some companies compensate their climate footprint by supporting projects around the world that either mitigate emissions of greenhouse gases or remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. The common term for this is “carbon offsetting”. The intentions are praiseworthy, and it can certainly make sense to communicate about them to the public – but not by claiming to be climate neutral. A statement like this is more truthful: “Our climate footprint is XX kg CO2e. We are working on reducing our greenhouse gas emissions. We are also investing in project YY that we believe can contribute to the fight against climate change.” This is the honest and transparent way.

Why then, does the positive not simply cancel out the negative? There are two main reasons.

1: It is very hard to know how large an effect the projects really have. In many cases, they do not even seem to work at all.

2: There is a clear risk of double counting, meaning that several parties take credit for the same emission reductions or greenhouse gas removals.

Let us take a deeper look at these issues.

Newsletter to-go?

Our special today is our Newsletter, including snackable tips, hearty climate knowledge, and digestible industry news delivered to your inbox

Does carbon offsetting work?

This is the million-dollar question. In some cases, it is inherently hard to assess. In other cases, we know that the answer is no. For each project, we need to ask ourselves the following:

- Does the project deliver the intended results? Things do not always go as planned. A large project in Kenya invested in energy-efficient stoves. As it turned out, most of them were never used. Still, climate offsets were certified and sold. For other projects, we will not know the outcome for a very long time. Planted trees, for instance, only absorb and store carbon as long as they are not cut down. How can this be a year-long guarantee in countries such as Uganda, globally top-ranking in corruption?

- Is the project “additional”? In some cases, the project would have taken place anyway, even without the carbon offsetting contribution. Wind power farms, for instance, produce carbon offsets on the assumption that the electricity produced replaces coal power. But many of the countries that host these projects are growing economies with a steadily increasing energy demand. The wind power farms would probably have been built anyway.

Additionality is generally an explicit requirement for a carbon offsetting project. But unfortunately, the analysis of whether a project is additional is often highly subjective and hard to evaluate in a transparent way. A German research study (Cames, 2016) found that only 2% of the investigated projects were highly likely to be additional.

- Is leakage avoided? Leakage is when greenhouse gas emissions increase in another area, because of the carbon offsetting project. If trees are planted on land used by the local population for forage or agriculture, this may lead to cutting other trees down elsewhere: The local farmers may have no other option than to clear vegetation at a new location to continue their agricultural activities. This becomes at best a zero-sum game for the climate but a loss for the farmers who need to move, and a loss for biodiversity since planted forests host less biodiversity than natural vegetation.

Who takes the credit?

This is the second question we need to ask. In the business of carbon offsetting, it is not unusual that more than one party takes credit for the same action, resulting in deceptive bookkeeping. Take the following example: trees are planted in Uganda as a carbon offsetting project. Company X buys the carbon offsets and label their products as “climate neutral”. This means that company X takes credit for removing greenhouse gases. However, it is not unlikely that Uganda also accounts for this tree planting in the national inventories of greenhouse gas emissions. In this case, the action is double-counted.

Let’s take another example. A wind farm is built in Brazil. A company buys carbon offsets on the assumption that electricity replaces coal power. Avoiding double counting means that Brazil will have to assume that the electricity produced comes from coal power, although it actually comes from wind. This does not lie in the interest of Brazil, which has targets to reach under the Paris agreement. With a certain amount of sold carbon offsetting credits, Brazil could end up in a situation where they have only renewable energy in reality but would need to keep on reporting as if they had only coal power since they have sold the right for the emission reductions to other parties.

The negotiations of the Paris agreement showcase how difficult it is to agree on rules to avoid double counting. Reaching our climate targets requires that we BOTH reduce emissions in all countries around the world AND remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, for instance by planting trees. Double counting blurs our vision and makes it harder to keep track of what remains to be done.

If we look specifically at the food industry, we see that it is currently responsible for about 25% of global greenhouse gas emissions (IPCC, 2014). To fulfill the Paris agreement and stop climate change, the industry still needs to reduce their emissions, even if the remaining 75% from other industries shrinks to zero! Crediting the food industry with reductions in other sectors cannot be the solution and such claims have the risk of delaying real and effective measures.

What do we suggest?

There are technologies that you could argue actually work. One example is direct air capture, i.e. facilities that capture carbon dioxide from the air and storing it below ground. It is a technology with a high probability of giving the intended results as it is highly unlikely that the carbon dioxide will escape underground storage. It is a costly technology with no other positive side effects. Therefore, it can be “additional” since it will not exist unless someone pays for it. There are other climate compensation technologies that are arguably effective and we cheer any engagement in such projects. Nevertheless, our basic appeal is this: The most effective way to put a stop to climate change as a food producer is to discover your precise climate footprint (and consequently take actions to lower it) and communicate it to your customers without smokescreen. CarbonCloud is here to help!

Cames, M., Harthan, R. O., Füssler, J., Lazarus, M., Lee, C., Erickson, P., & Spalding-Fecher, R. (2016). How additional is the clean development mechanism. Analysis of application of current tools and proposed alternatives. Oeko-Institut EV CLlMA. B, 3.

IPCC. (2014). Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1454.

Related Posts

How to assess the quality of a carbon offset

Carbon offsets are created in a space of uncertainty and nuances. Historically, these shades of gray can sway either way to create attractive, marketable commodities. Far too frequently it has the opp

🇬🇧 Green Claims Code: Unpacking environmental claim requirements

Last September, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) of the UK issued a guide on environmental claims. The guidance lists the requirements of what a product, brand, or service may claim regardi

Can the food sector reach Net-Zero?

Net-zero seems to be the ultimate goal for the food sector – and the whole world for that matter. Pledges, commitments, targets live proudly on corporate websites and net-zero is now a long-term KPI

What makes a carbon offset?

One thing for us to say “a product cannot be carbon neutral” and expect you to take our word for it and another to present the facts. So we took the time to present the full argument in an article