The great debunking of climate myths: Transportation

Enjoy this ribeye steak, friend! Yes, its carbon footprint is infamously high but don’t worry; I buy all my beef from local farmers.

Hey roomie, when you get to the grocery store, get the local tomatoes! They’ve traveled less.

Does it sound familiar? It’s no surprise. The climate impact of food transportation is such a hot topic that it has almost 3 million results on Google, several apps and calculators, and its own name: ‘Food miles’. Do food miles matter for the climate? Let’s examine the intuitive pop narrative.

Climate Impact: Food Production vs Food Miles

We could say that what’s to follow is old news but given the popularity of ‘food miles’, we can’t really be sure: Agriculture accounts for the large majority of greenhouse gas emissions from food. On average, agriculture amounts to up to 83% of the total emissions from food [1, 2]. And what about transportation? On average, transportation accounts for less than 10% of the total greenhouse gas emissions of food [2, 3]. How does this data look for the ‘Eat local’ lifestyle? Buying all-local food will reduce your footprint by 5% – maximum.

Climate Impact: Food Type vs Food Miles

Naturally, the percentage of transportation is relative to the total carbon footprint – or better yet, climate footprint – of the food product. For certain food categories with a high climate footprint, beef being the prominent example here, transportation emissions can even be negligible.

Let’s have a chat with your friend who presented the local ribeye steak at dinner as climate-competitive. The climate footprint of beef is so exceedingly high in comparison to its transportation that your friend managed to save less than 1% of the emissions of your dinner. For a climate-competitive decision with an impact, had they replaced the calories of this single weekly ribeye dinner with poultry, fish or a plant-based alternative, your emission savings would be higher than eliminating every single food mile that week [1]! The verdict is in: What you eat matters more to the climate than where you get it from.

Food type vs food miles: The other side of the coin

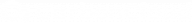

With beef being at the other end of the spectrum, it’s quite easy to make a favorable point. Let’s examine the other end of the spectrum, the one with very low emissions: Fruit, vegetables, and legumes. If you take a look around our carbon footprint benchmark library in Climate Hub, you may find that up to 60% of the climate footprint for certain products is transportation.

The reason here is simple and it still touches upon the type of food. The percentage of transportation – or any stage of the supply chain – is inversely proportional to the total climate footprint. So, the lower the total footprint of the product itself, the higher contribution ‘food miles’ or transportation have on its climate footprint. Conversely with beef, the higher the total footprint of the product, the lower food miles contribute to its footprint.

To put climate impact back in focus, if one cares about their emissions, it’s still the type of food that matters to our personal climate footprint. The verdict on food miles vs type of food still stands.

Newsletter to-go?

Our special today is our Newsletter, including snackable tips, hearty climate knowledge, and digestible industry news delivered to your inbox

Climate Impact: Geography vs Food Miles

Nevertheless, the type of food is not the only factor. There is another significant factor of great importance and it surfaces with the commonly innocent fresh produce: The conditions under which the food is produced matter too. Certain soils and climates are better suited for specific crops. However, with our lifestyle today, not all latitudes can support this localization. Also, the global food trade is not ‘a sign of our times’. In fact, crop adoption has been a reality throughout the eras. Today’s staples like potatoes and tomatoes were introduced to Europe from South America by the conquistadors. Regardless, as technology developed with greenhouses, irrigation, and fertilizers, humanity has overwritten the geographical parameter – with implications for the climate footprint.

Let’s take your roommate’s request for local tomatoes. Tomatoes are impossible to grow in colder climates and if you live in one, chances are that your local tomatoes, slim on few food miles, are greenhouse-grown. And it’s no matter if they are not in season, since warmer climates have winters too (they do!) and greenhouses are necessary there as well. Still, tomatoes need high temperatures, which means that a greenhouse in a colder climate requires additional heating; additional heating requires additional energy. The effect of the additional energy? A sixfold to elevenfold increase in climate footprint!

The results are staggering: Tomatoes less traveled but grown in a British greenhouse that requires auxiliary heating have a climate footprint of 3.8 kg of CO2e. The climate footprint of the same tomatoes, grown in a greenhouse that doesn’t require heating in Spain is 11 times smaller: 0.3 kg of CO2e. And the climate footprint of the Spanish tomatoes food miles? A mere 5%. Your roommate may need to knock the ‘food miles’ trophy out of the climate display…

Climate Impact: Transportation Mode vs Food Miles

Now, there are cases where transportation has a large impact on the climate footprint of food: Air freight. Bad news is, air freight is rarely indicated on the store shelf. Good news is, it is safe to assume that your food has been transported by air if it’s fresh, off-season, and highly perishable. Generally, avoid off-season berries, asparagus, green beans, cherries, and flowers (commonly not a food, but we don’t judge).

However, it’s important to note that air freight is not as common as one might assume. In fact, air freight accounts for 0.16% of the total food miles [4]. It’s even more important to note that there are climate-friendly ways of transporting food – and they are widely used in the industry! Approximately 60% of food is transported by boat, which is the mode of transport with the least emissions. Water transportation is followed by road at 30% and rail at 10%. So yes, transportation may be a factor – not in miles, but in mode.

Verdict: Eating local won’t save the climate

The results are in and with a score of 4-0 and the myth is busted: Food miles or ‘buying local’ have a minuscule climate impact. The type of food, how it is produced, and how it is transported are factors with a significant climate impact.

That is not to say that eating local is an irrelevant preference. Consumers may see other environmental, social, or financial benefits in buying local food, each with lengthy and often factually inconclusive debates of their own. However, the claim that reducing food miles reduces greenhouse emissions can be two things: greenwashing …or misinformation!

Related Posts

Nordic Seafarm: A jack of all trades ingredient, an ace in climate performance

What’s your first thought when you think of seaweed? And no, it can’t be maki rolls! Nordic Seafarm is here to make Nordic sugar kelp the top-of-mind ingredient. Multifaceted, bringing a wave of u

Comparing apples & oranges: Climate footprints of 10,000 food products revealed

ClimateHub, the free-access carbon footprint database by CarbonCloud, digitally releases the climate footprint of 10,000 branded food and beverage products at the American grocery store shelves. Ahead

‘Best in class’ comes with the burden of proof

A climate footprint assessment can be done for many different reasons and with different levels of ambition. Climate change is a serious problem. It is now getting the merited spotlight, and we cannot

How do deforestation emissions work in food?

Deforestation is one of those topics that, as actionable and measurable as it is, transcends business and numbers. For most of us, images of thinning forests, the faded shades of green over the Amazon