Climate footprint labels: Why we use the number – and why the entire food industry will too.

The quantitative and specific climate footprint label may still be perceived as disruptive but we are certain that there simply isn’t a way that is more informative and transparent to communicate the climate impact of food. We don’t have to look far to see that quantification is the only solution that stands the test of time in global markets and is factual enough to permeate regulation. Here’s why.

For the years CarbonCloud has been active, and for years before in the research sphere, we have seen verticals completely transform triggered by climate initiatives; climate best practices turn into regulation embryos and further into legislation. Within the food industry, we have seen sustainability communication schemes come and go; measurement scopes and reporting standards being a must-have – for a year or two until they fade back into obscurity; As an organization, we have been advising customers against vague communication choices, only to have authorities prove the advice right.

With humility, openness, yet with historical confidence, we can say that one thing stands the test of time and prevails over time and maturity development: Objective, absolute quantification, and transparency.

Several historical and present examples confirm the pressing need and the certain establishment of quantified climate impact. The most analogous example comes from within the food industry, and it foretells the development of the label.

The nutritional information example

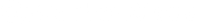

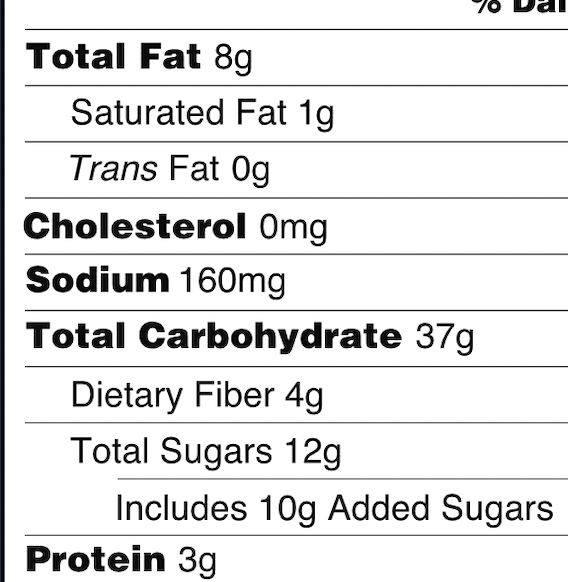

During the ‘60s Americans started shifting their diet from cooking meals from scratch to consuming prepared products – what is commonly called the “tv dinner”. The opacity of what these meals contained raised health concerns among American consumers who demanded transparent information. To respond to this high consumer demand, in 1966, the USDA mandated the use of ingredient lists in commercially available food products.

Alongside the mandatory ingredient list, many food companies started including health and nutritional claims. These claims were usually of a qualitative nature and mostly aimed to comfort consumer concerns. However, still unregulated, many of these claims were misleading or had little to no scientific ground. In 1973, misleading and false health claims became so frequent that the issue reached the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court resolved the issue with the ruling mandating the substantiation of voluntary health claims with quantitative nutritional information by weight [1].

In the years between and until 1990, food producers voluntarily displayed nutritional information in a non-standardized way. Meanwhile, as dietary concerns were piquing the regulators’ interest and consumers became more sophisticated, so did the nutritional claims on food products. At this point, health claims with undefined nutrient content such as “low-sugar”, “low fat”, “low cholesterol”, “high protein”, which were mandated to coexist with the nutritional facts became popular.

The 1980s saw a peak in filing of deceptive claims highlighting the need to regulate nutritional information further. The result? The FDA’s Nutrition Labeling and Education Act, where nutritional information and the content of the label became quantified, consistent, standardized, and mandated for all food products sold.

Newsletter to-go?

Our special today is our Newsletter, including snackable tips, hearty climate knowledge, and digestible industry news delivered to your inbox

Where “nutritional information”, read “climate information”

The climate information label is unfolding in the same footsteps as the nutritional label. At the moment, climate communication on food products is living on the ’80s point of the nutritional label, making vague or blanket claims without the specific data to back them up.

What has happened in the previous decades?

In 2015, the world decided to solve climate change and do it seriously. The global community signing the agreement committed to doing so. Many industries in the eye of the climate storm, such as the energy sector and the automotive industry, have looked at their emissions data, rapidly transitioned away from emissions and fossil fuels, and made a good profit doing so. Citizens are also on board, trying to minimize their climate impact and demand the relevant information from their purchases.

Feeling the global pressure of the 2030 deadline approach and to respond to this demand, the food industry is dipping its toes in communicating its climate initiatives. In the past 10 years, food companies started making sustainability claims to appeal to conscious consumers with various degrees of specificity: Some years back, a mere “green” or “eco-friendly” claim was doing the trick.

Where are we now?

The food industry on average is at the maturity level of claims such as “carbon neutral”, “green-amber-red”, “climate positive”, still unfortunately lagging behind other industries. Meanwhile, 35 of the world’s most prominent economies are mandating disclosures on corporate climate strategy, emissions, targets and roadmaps. The consumer base is concerned about the information on the climate impact of food, with the largest concern (22%) being lack of trust and greenwashing concerns.

At this point in time, reminiscent of the 1980s of the nutritional information timeline, these vague and too-good-to-be-true statements discredit trust in all claims and ambitions in a dangerous way

Where “misleading”, read “greenwashing”

- 42% of environmental claims in a global review by the International Consumer Protection and Enforcement Network (ICPEN) were found eligible for greenwashing [2].

- In the German market, Aldi, one of the largest retailers globally, is facing public backlash on the use of a “climate neutral” label on milk [3]. The backlash has prompted other companies in the German market, including the FMCG giant dm to discontinue the same “climate neutral” claim provided by the same partner [4].

- The European dairy leader, Arla, also faced a huge backlash on its “climate neutral” campaign, leading to a lawsuit from the Swedish Consumer Agency for misleading claims. The backlash continued strong with Arla now withdrawing all offsetting strategies and investing in reduction initiatives instead [5]

- France is regulating the term “climate neutral” and other terms with equivalent meaning or scope with stricter criteria [6]. According to the Climate and Resilience Law, effective August 2022, companies cannot claim carbon neutrality for their products unless they have the following information transparently and publicly available:

- GHG emissions report for direct and indirect emissions at product level

- Processes for product emissions avoided, reduced, or offset as well as a reduction plan

- Offsetting methods with details of the arrangement including the nature, the description, and the cost of the offsetting projects

The undefined emissions content claims

Just like the “low-fat” labels of the 80s, some food brands choose to display the climate value of their products in relative terms, more specifically, color coding. But the nutritional déjà vu of color coding comes from the European history of nutritional information.

To answer whether the color-coding system is efficient in communicating climate information, we can look back at its implementation in nutritional information, with Nutriscore. NutriScore was a color coding and scoring scheme adopted by France, the UK and a few other European countries in the ’00s to help consumers make informed decisions on their nutrition.

In 2008, Nutriscore was considered by the European Commission for nutritional information, but the initiative was abandoned in favor of quantified information on energy, fat, saturated fat, and carbohydrate content per 100 ml or 100 g or per portion. In his explanation, Markos Kyprianou, the European commissioner for health at the time, said that it “oversimplified” nutritional information, adding “what we want are informed consumers” [7].

A meta-analysis of Nutriscore labels with the color coding on packaged products showed inconclusive results on affecting consumer behavior [8]. Another study using Nutriscore as an A-E grade at the grocery store shelf tags, concluded that it was on its own unlikely to influence consumer behavior [9]. These results confirm Kyprianou’s choice of what is an informed decision.

Will color coding fizzle out in the history of climate labels?

Color coding poses the same problem for climate information as it does with nutritional information: It is not sufficient information or transparent enough. As a society, at the moment we are at the maturity level of exploring the problem of what is sufficient and transparent information on climate performance. The color-coding scheme may develop into two scenarios – both leading to a dead-end in application.

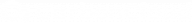

- In the first scenario, emissions are color-classified in absolute terms, meaning from highest to lowest regardless of the type of food – one scale covering all food products. In these cases, the difference between a high climate footprint and a small one is so big that it cannot be captured with a scale of 3 or 5 colors. The only information the consumer gets in this scenario is that red products are most likely in the beef or crops with a high deforestation rate category, amber products are cheese or pork, and green products are pretty much everything else.

Consumers still cannot tell the beef with the best climate performance from the beef with the worst climate performance – marked red, they can only understand that it is beef, even though one may have twice the emissions of another. - In the second scenario, the color coding may apply to each specific category of food. In this case, consumers may be able to tell “good beef” from “medium” and “bad beef”. Consumers may buy green beef and red orange juice. However, the climate footprint of the “greenest” beef is still ten times higher than the “reddest” orange juice and with color coding, this information still eludes consumers.

Instead the information they get is that they are solving the problem with one “green” beef and they disregard the problem with 10 “red” vegetables. The fact remains that 10 “red” vegetables amount to one “green beef” – but the consumers are not sufficiently informed to make a relevant choice. They are as informed about how many calories they got from green butter and red banana.

- In the first scenario, emissions are color-classified in absolute terms, meaning from highest to lowest regardless of the type of food – one scale covering all food products. In these cases, the difference between a high climate footprint and a small one is so big that it cannot be captured with a scale of 3 or 5 colors. The only information the consumer gets in this scenario is that red products are most likely in the beef or crops with a high deforestation rate category, amber products are cheese or pork, and green products are pretty much everything else.

Has the label fulfilled its purpose of helping consumers make informed decisions? Herein lies the “what next?” of pre-evaluated climate information.

What is the next chapter for climate labels?

As with any other label and much like the nutritional label, the survival of the climate label beyond marketing depends on a single question: Does the label help the consumer make an informed choice? The answer to this question involves 3 stakeholders:

- The food industry, presently exploring the limits of climate claims – what an informed choice is and what isn’t.

- The consumers, becoming more educated themselves and feedbacking on what is an informed choice and what isn’t.

- Legislation, chastising misinformation and standardizing the informed choice.

There are many examples from the market history where quantification -of what is quantifiable- prevailed. Today we explored in depth just one, the most relatable one for the food industry. At CarbonCloud we chose quantified climate information from day one, with profound acceptance of 3 points:

1) We will have to stick through the food industry maturing.

2) This is where the regulation ball will drop: The single number that bares all the relevant information. The climate footprint.

3) The food industry will catch up. The leaders of tomorrow will climate-footprint their products today and work on getting the numbers down – they win today in communications and tomorrow when emissions policies are up and running. The followers will come tomorrow and we’ll be there to help them heal their wounds.

AT THE END OF THE DAY...

It's really not about the label

No one taking climate change seriously thinks that labels will solve the problem, regardless of how pretty or rich in information they are. That is not why we help food producers climate-label their products.

Related Posts

Sysco Subsidiary Menigo Applies CarbonCloud Machine Learning to 23,000 products

Menigo launches its largest climate data initiative ever in a new partnership with CarbonCloud. The startup’s climate intelligence platform calculates the footprint of the entire product portfolio w

‘Best in class’ comes with the burden of proof

A climate footprint assessment can be done for many different reasons and with different levels of ambition. Climate change is a serious problem. It is now getting the merited spotlight, and we cannot

It is not about the label

For most, the first touchpoint with CarbonCloud is the climate footprint label. But we do not spend our waking hours providing a climate change participation trophy. We want to generate real change i

Comparing apples & oranges: Climate footprints of 10,000 food products revealed

ClimateHub, the free-access carbon footprint database by CarbonCloud, digitally releases the climate footprint of 10,000 branded food and beverage products at the American grocery store shelves. Ahead